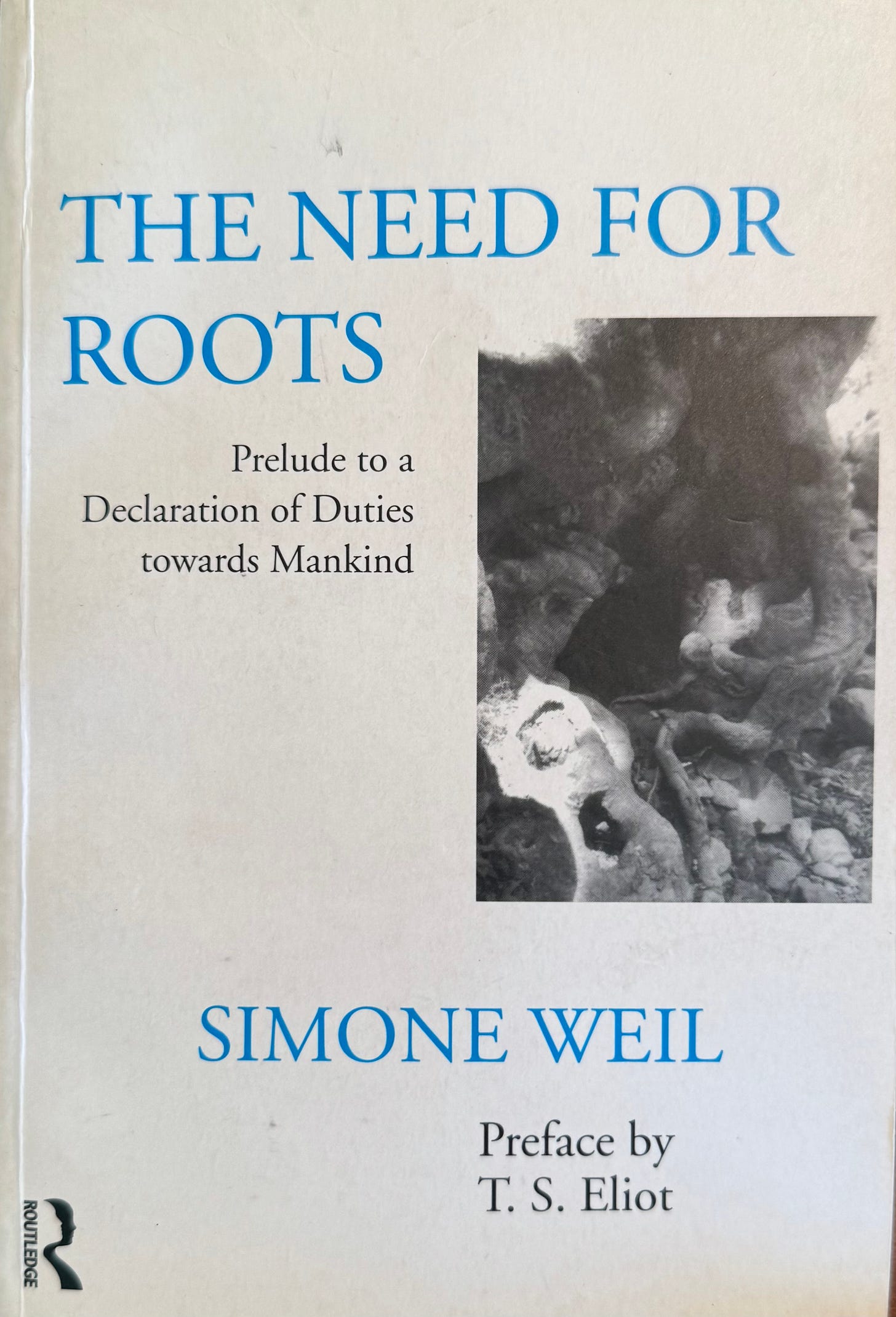

The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind

A Meditation on a Book by Simone Weil

“To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul.” —Simone Weil, The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind

I’m at the wheel of my mother’s car with my elderly mother in the passenger seat. We are running errands and poking along on a six-laner through the vast sprawl of Jacksonville, Florida. The road is swarming with speeding traffic and afflicted on both sides with shopping malls, office parks, condominium developments, and warehouses.

Not long ago this land, like much of the Southeast, had been fields and farms and swamps. But the fields and farms and swamps had been filled in and paved over and built upon to capitalize on the swelling ranks of people of all ages moving here from all over the country as though at the end of a huge funnel. Around that time, the early 2000s, the Sunshine State’s population was growing at a rate about double the national average. My parents were just two among that multitude of transplants—in their case, retirees—many of whom surround us now.

“Where are we?” my mom asks apropos of nothing, while looking around at the maelstrom whizzing by in the glaring heat outside our air-conditioned car’s windows. I glance at her. Never a large woman, she appears smaller now on account of her years. And I swear she appears to be sinking into the oceanic, anonymous chaos all around us.

“What do you mean?” I ask. We’ve been on this road many times before. I say, “You know where we are.” I think, with a fright, that maybe she is losing her mind. Dementia, that’s what I’m thinking. Is this how it starts? Small slips of disorientation.

“Not like that,” she says. “I mean, what is this place?”

I feel her perplexity as my own. I feel “lost” here, too. Ungrounded. Uneasy. What is this place? We could be just about anywhere in the country; there are no defining features to indicate that we are anywhere unique. Where I live, in the Hudson Valley of New York, there’s the same scourge of urban and suburban sprawl. But the scale is smaller, more contained, and even easily avoidable if that’s something you want to do. There’s still plenty of nature around in which to seek solace. But not here. There’s no escape; you could drive for hours and still never find your way out of this same mind-numbing morass, drained of the natural world but for the ragged palmettos that occasionally dot the median strip that separates the opposing lanes of traffic.

Born in the Northeast, I spent most of my youth in an early American exurban pocket of Connecticut. Now, in the nearly 40 years that I’ve lived in the Hudson Valley, I’ve sown my own roots here among similar remnants of old architectures, storied histories, and bumpy, winding roads among which I was raised. I like it. I could even say I need it. And I’ve cherished living among the spirits of my ancestors on my mother’s side of the family who, as members of the Continental Army, fought the British in the Revolutionary War in these parts. My small house—a former gatehouse to a still-extant 19th-century Hudson Riverfront estate—is just a mile from a historic site and house that belonged to one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. He is entombed in the graveyard of the old stone church next door to me.

For most of their lives, my mother and father, too, lived in the Northeast. My guess is that in this moment my mother is not feeling rooted someplace or connected to anything meaningful in her life. I can almost feel as if we’re tumble weeds surrounded by more tumble weeds, all of us just blowing in the prevailing wind. With nothing around us now to remind her of where she’s from, of where her lineage fits into the nation’s history, perhaps it’s my mother’s ancestral memory that’s drawing a blank. Yet, she knows exactly where we are: Somewhere in the middle of nowhere.

I despair for her. She has reached an age when you want to feel secure in, and at ease with, your place in the universe—a feeling of being held, if you will, by family and friends—yet now she appears to feel more emotionally orphaned than I’ve ever noticed before. It is strange to think of your mother or father being orphaned. But how else to put it? There is no one they can count on for regular, familial support; nothing beyond the physical comfort they’d sought all of their adult lives and have now achieved. But gained at the expense, it turns out, of no longer feeling at home anywhere. Which is to say there are other ways to feel orphaned besides having no parents. And there are other ways to suffer the blight of homelessness besides not having a roof over your head.

It has been a long road getting here. My father spent his working life seeking promotions in order to earn more money so that he could buy ever-larger houses to accommodate our growing family. Sometimes we picked up stakes and moved not just across town but to other towns and, once, to another state. And these moves, I think, disrupted the bonds of neighbors and friends we’d all had forged individually and as a family—my parents, my three brothers, and I—wherever we had settled. We didn’t move a lot but we moved just enough—and perhaps at critical times in my and my siblings’ psychological development—to fracture our developing internal cohesion and sense of having any sort of solid ground beneath our feet or allegiance to place.

The moving had taken a toll on our familial bonds as well. Since 1973, when my father relocated us from our beloved home in Connecticut to accept an executive job running a struggling brass factory in Michigan, I can recall only two times when my parents and their four sons gathered under one roof for a family celebration or holiday. Which is to say that we’ve never been a close-knit family, in part because of how we grew up and in part because of where we all ended up, which may be a consequence of how we grew up.

While I’m in New York, I have a brother in Colorado and another brother in Michigan. We also had a brother in Maine, but in December of 2022, he died at age 65. (I wrote about that here.) He never married and moved several times in search of satisfying work in graphic design and advertising, and for a place where he might feel rooted, which turned out to be the Maine coast. It was there that he spent his final years living in a roughly finished, walk-out basement of a house owned by a cousin of ours in Cape Elizabeth, yet still the most lost and alienated among four brothers.

***

Simone Weil was a French philosopher who, during WWII, had been commissioned by General de Gaulle, head of France’s government in exile in London—Free France—to write a report on the duties and privileges of the French after their liberation. This report was intended to outline options for reviving France after an allied victory, which was imminent but still a year away. This report was published in book form in 1949 in French under the title of L’Eracinement, six years of Weil’s death in 1943. It was published in English in 1952 as The Need for Roots: A Prelude to a Declaration of the Duties of Mankind. In it, she writes:

“A human being has roots by virtue of his real, active and natural participation in the life of a community which preserves in living shape certain particular treasures of the past and certain particular expectations for the future. This participation is a natural one, in the sense that it is automatically brought about by place, conditions of birth, profession and social surroundings. Every human being needs to have multiple roots. It is necessary for him to draw wellnigh the whole of his moral, intellectual and spiritual life by way of the environment of which he forms a natural part.”

What Weil is saying here is that it’s not enough to feel rooted to a particular place or to the community in which we’ve found ourselves. We also need to feel rooted to a shared history, to a common language, to a moral standard, to our work, to obligations, to some sort of spiritual life. She believed France was suffering from this lack of roots both before and during the war and wrote in The Need for Roots what she believed would help get France back on its feet.

I’m writing about this now because it appears to me that there are certain aspects regarding what happened in France before and during the Nazi occupation that are similar to what we have faced in this country before and during another kind of occupation—an insidious amalgamation of communism and chaos and corruption—which boiled over the bounds of common decency during the unfathomably fraudulent Biden regime, an occupation that sought—and to a great degree temporarily succeeded—in the decimation of so much our country that Weil also lamented had happened in France. Both countries suffered from a malady of uprootedness that weakened both individual and collective resilience and left them open for an invasion.

But, just as there are similarities, there are also differences between the Nazi occupation of France and the despotic occupation in America over the past several years. One is that it was usually obvious during the occupation of France who the adversaries were. For one thing, they’d come from another country and spoke another language. And they wore uniforms. During the occupation of this country, the conspirators were—and remain—not so obvious. The Luciferian operatives of the current occupation gathered their conscripts from tens of millions of ordinary Americans who had—and continue to have—no idea of the breadth and depth of the occupation of which they are a part. Nor do they have any inkling about its intention or how long it has been slowly infiltrating every nook and cranny of American life. As a result, this occupation has had on all of us a far more destructive ideological force than America has ever faced from a foreign invader.

What began, for example, in the 1990s in the stealth fog of “political correctness” in America, has mutated into our current monstrous “cancel culture” and gaslighting. “The tag itself, I have come to realize, creates a linguistic cul-de-sac where we just park our brains,” writes Diana West in her brilliant 2013 opus, American Betrayal: The Secret Assault on Our Nation’s Character. “‘PC’ is, gosh, ‘PC.’ We look no further. Sure, the acronym, ‘PC’—'political correctness’—conveys the idea that something is phony, forced, and ideologically, not logically, inspired, but it doesn’t advertise its bona fide totalitarian provenance in the language of ideology, which, once accepted, once internalized, draws an individual into that ideological pact with the devil in which reasoning powers are lost. [Italics mine.] In other words, ‘PC’ is just another label for Big Lies—little lies, too. It describes the systematic suppression of fact that advances and sustains the ideology of the State and its barricades in academia, media, and other cultural outposts.”

Weil might have naively flirted with the Big Lies and little lies of the State totalitarian ideologies of her time, which then—as now—was embodied in communism. After all, it was de rigueur among the so-called intellectuals in France—the likes of leftists Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir—lingering over glasses of Burgundy in smokey Parisienne cafes in the 1930s and 1940s. But Weil eventually learned how foolish Karl Marx’s idea was about the “dictatorship of the proletariat” leading to a more egalitarian if not utopian civilization.

In The Need for Roots, she called Marxism “a completely outlandish doctrine.” Robert Coles in his 1987 portrait of Weil, Simone Weil: A Modern Pilgrimage, writes, “She knew how unlikely, how absurd such a notion was. She knew, morally, what ought to be, but she knew as a slave, as a brilliant slave, how oppressive force is on anyone’s life, and on society.” All anyone had to do to learn about the abject failures of Marxism was to dig a little and find out what was happening under Josef Stalin’s murderous hand in the U.S.S.R. not all that far as the crow flies from those glasses of Burgundy in those smokey cafes. But then, like now, there’s mysteriously little motivation among certain people—most people, I’m beginning to learn—to acknowledge the truth if it compromises or challenges their ideology.

Not so Simone Weil. Coles writes: “The Need for Roots, with its sketches of a postwar world, a France of her dreams, she not only used the metaphor of rootedness; she tried to spell out ‘the needs of the soul’ if an undermining, disheartening uprootedness were not to develop. Her recitation of those needs amounts to a remarkable conservative manifesto, a powerful statement on her part with respect to politics and social institutions.” He goes on to say that Weil “detested the proudly amoral or value-free partisans of the liberal and radical intelligentsia.”

In his preface to the first English translation of the book, published in 1952, T.S. Eliot writes that “she appears as a stern critic of both Right and Left; at the same time more truly a lover of order and hierarchy than most of those who call themselves Conservative, and more truly a lover of the people than most of those who call themselves Socialist.” He goes on to say that Weil was “by nature a solitary and an individualist, with a profound horror of what she called the collectivity—the monster created by modern totalitarianism. What she cared about was human souls.”

Here, so successful was the complicit mainstream media in getting vast swaths of the American population to go along with the big and little lies of the totalitarian ideology of the State in our times, which came to head with the COVID-19 psyop, that the complete conquest of America was at hand. And it was not happening through any sort of armed conflict, but rather via government orchestrated, insidious pathways into the mind through widespread censorship and narrative control, and all of it dominated by fear. Tens of millions of American minds had been captured and convinced that anyone—people like me and perhaps like you, too—who have done what we could to stand in the way of this tyrannical takeover, perhaps only by asserting our right to refuse the toxic COVID-19 jabs—had become, at the flick of a switch, the enemy.

And all it took was a complicit media to spin the lies big and little, a phenomenon of which Weil, too, was well aware. She writes in The Need for Roots:

“We all know that when journalism becomes indistinguishable from organized lying, it constitutes a crime. But we think it is a crime impossible to punish. What is there to stop the punishment of activities once they are recognized to be criminal ones? Where does this strange notion of nonpunishable crimes come from? It constitutes one of the most monstrous deformations of the judicial spirit.”

***

The Nazi occupation of France had begun in May 1940 when France was invaded by German forces. The occupation ended in Paris in August 1944. By the latter part of that year, all of France was free. So, Weil was writing during the occupation while she was living in London, itching to get back to France to fight with the French Resistance, but unable to do so because of her failing health—she struggled with poor health throughout her life and was tormented by migraines—which might have been exacerbated during her brief involvement in 1936 on the harsh battlefields of Spain while fighting with the Republican forces against Franco’s Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War.

One time on the front along Spain’s Ebro River, Weil, nearsighted and clumsy by nature, accidentally stepped into a large vat of hot cooking oil. In her biography of Weil, Simone Pétrement writes in Simone Weil: A Life of her and her fellow soldiers:

“They were still bivouacked in the bushes, on the right bank of the Ebro. They had started a fire in order to cook their meal in a hole dug in the ground, so as to screen any flames that might have given their position away. A huge pot or frying pan had been place at ground level over this fire of covered coals. Simone did not see it and put her foot right into the boiling oil. Her foot was protected by her boot but the lower part of her left leg and the instep were seriously burned.”

There is no telling what Weil might have accomplished had she joined the Resistance in France instead of writing in London. She was given an office on her own but never intended to give up her intention to get back to France to take on more dangerous missions. What we do know is that whatever dedication and energy she might have poured into the Resistance movement in France, she gave to her writing in London. “She was boiling with ideas,” writes Pétrement. “The sheer amount of what she wrote in London in a few months is almost beyond belief. She must have written day and night, scarcely taking the time to sleep. More than once she spent the entire night in her office, where she voluntarily locked herself in.”

***

Born to affluent, agnostic Jewish parents (her father was a prosperous medical doctor and her mother a housekeeper) in her parents’ Paris apartment on February 3, 1909, Simone Weil was something of a child prodigy and, during her 34 years on earth, became a formidable if not insufferable champion of the downtrodden, of freedom, and of human dignity. At age six, she could quote passages of Racine by heart. She was proficient in ancient Greek by age 12 and she later learned Sanskrit (along with her brother) so that she could read the Bhagavad Gita in the original. She received her baccalaureat es lettres, the equivalent of a high school diploma in the United States, at the age of 15. Her own feelings of uprootedness, which would turn out to trouble her for the rest of her life, must have begun around this time. During those early years, her father was enlisted in the French army to fight in WWI, and the family followed him to different fronts throughout France.

She graduated college at 22 as a teacher of philosophy. She started out her career teaching in the small city of Le Puy but then joined the ranks of laborers in factories, on farms, and on vineyards—work that she undertook to learn about, and align herself with, the lives of those less privileged than she was. After the German invasion of France, she and her parents and her brother André, who was her elder by three years and also a child prodigy who would later become a renowned mathematician—and compared to whom Simone felt intellectually inferior—fled to Marseille in 1940 to await permission to sail to the United States to escape the Nazi exterminators. More than anything, however, Weil longed to join the French Resistance. She thought that after she’d helped her parents to safety and get them settled in America—she knew that they would never leave France without her—she could then go to Britain and, from there, return to France as a covert agent.

To her credit, she eventually did reach Britain in the late autumn of 1942—the crossing from New York to Liverpool aboard a Swedish freighter with only 10 passengers took 10 days—but was limited to desk work in London analyzing reports from resistance movements. She wrote all sorts of essays focusing on politics and religion and philosophy, but also about ancient Greece and even a translation of extracts from the Upanishads. Additionally, she worked on what would become The Need for Roots.

The book, it turns out, would become her final testimony as to what she felt were the most vital needs of human civilization—and also of what she herself had lacked most of her short and turbulent life. It was a work that Pétrement in her biography of Weil describes as “the new and difficult task of defining this need and searching for the means by which it could be satisfied.” With her exceptional analytical mind, Weil had reached the conclusion, based on what she experienced, what she knew of history, and what she was witnessing in France from afar, on how uprootedness comes about. This report evolved to become The Need for Roots. In it, she concludes: “Uprootedness occurs whenever there is a military conquest and in this sense conquest is nearly always evil.” She writes:

“Conquests are not life, they are of death at the very moment they take place. It is the distillations from the living past which should be jealously preserved, everywhere, whether it be in Paris or Tahiti, for there are not too many such on the entire globe.

“It would be useless to turn one’s back on the past in order simply to concentrate on the future. It is a dangerous illusion to believe that such a thing is even possible…. The future brings us nothing, gives us nothing; it is we who in order to build it have to give it everything, our very life. But to be able to give, one has to possess; and we possess no other life, no other living sap, than the treasures stored up from the past and digested, assimilated and created afresh by us….

The past once destroyed never returns. The destruction of the past is perhaps the greatest of all crimes.”

***

As if that conversation with my mother in her car about her feeling lost was not enough to make me want to cry, my parents’ sense of uprootedness was driven home to me again during another conversation.

My father was a hard-working businessman of the post-WWII generation who strived above all else to be a reliable and fruitful provider for his family. Abandoned by his father to drinking and gambling and, finally, divorce, my father spent his own adult years compensating for that loss that haunted and relentlessly drove him right up until the moment when he was near his death. (You can read about that here.)

I can’t help but wonder now to what extent had he been enamored, if not captured, by the idea of upward mobility—”mobility” being the operative word here—at the expense of establishing roots in one place. This was not the result of any sort of military conquest. It was the result of an ideal that would have an entire generation of high achievers like my father put the accumulation of wealth above the planting of roots, an artificial construct that would inevitably lead many into domains of isolation and loneliness.

My father put in long hours, traveled a lot, and spent untold Saturday mornings at the office while his kids—my brothers and I—ran wild. He wasn’t around all that much to help my mother raise, and rein in, four rambunctious boys who seemed often enough to be up to no good. I remember a discussion at the dinner table about my father’s regular absence. He said he’d be fine working less, but if we wanted to continue to have the lifestyle we had, then his absence was what it cost the family. The rest of what I remember of that conversation was muted silence. I don’t recall anyone at the table voting in favor of him working less and bringing home less money. And that was the end of that.

“Even without a military conquest, money-power and economic domination can so impose a foreign influence as actually to provoke this disease of uprootedness,” Weil writes. “Setting aside the question of conquest,” she writes, there are “two poisons at work spreading this disease. One of them is money.” She continues: “Money destroys human roots wherever it is able to penetrate, by turning desire for gain the sole motive. It easily manages to outweigh all other motives, because the effort it demands of the mind is so very much less. Nothing is so clear and so simple as a row of figures.”

I would not go so far as to say, as Weil writes, that the “desire for gain” is as simple as she makes it out to be. She had, after all, no experience as a business executive. She could not have known that there would be an entire generation of young American men after WWII who would eventually give much of their lives over to that desire for gain, and it was not easy for them or their families. I know because I was there to see what was happening to all of us as if it seemed as natural and necessary as breathing. Yet, simplicity aside, if the pursuit of material gain outweighs every other aspect of our lives, Weil argues that it can—and will if not held in check—lead to uprootedness. And on that I would have to agree with her.

When my father partially retired in 1986 at the age of 64, due in part to a nagging, undiagnosed neurological malady, he and my mother moved (again) from Michigan to Savannah, Georgia. My father embraced his passion for golf, which he’d started playing on scrappy, public courses when I was not quite a teenager, and he was in his 40s. It was an adjunct to the office. I remember going out with him as a caddy and companion, hauling his golf bag on a pushcart. The golf course, he’d once told me, was where business friendships are forged and deals are struck. He perfected his game and enjoyed it so much that he played after he’d retired. Soon after, though, due to some botched surgeries on his shoulder and prostate, along with his other ailments, he played less and less golf and became less and less connected to his small group of fellow golfers. It was a turn of events that threw him off his game in more ways than one.

Thirteen years later in 1999, my parents sold most of their furniture, donated my mother’s cherished baby grand piano to a local church, pulled up stakes (again), and moved (again) to a large, assisted living facility amidst the vast, unchecked expanse of shopping plazas, fast-food joints, office parks, warehouses, and mini marts of Jacksonville, Florida. With the renowned Mayo Clinic just a few miles from their new residence—I can’t really call it “home,” although my mother always made fun of the place by calling it “the home,” alluding to a kind of old-age asylum—my father hoped he’d be better cared for by the doctors there than he felt he’d been in Savannah.

One Thanksgiving evening after they’d been there for several years, we watched a DVD of The Wizard of Oz that we’d borrowed from the facility’s small library, where my mother volunteered. I was alone with my parents this time, even during the nation’s most sacrosanct of family holidays. When the movie was over, my mother asked me out of the blue, “When you think of no place like home, what do you think of?”

“I don’t know,” I said, biding my time to mull over her question. “Maybe somewhere in the past, where we lived when I was a child. Someplace where I feel happy.”

“How about you?” she asked my dad.

“Anywhere but here,” he grumbled.

“How about you?” I asked my mom.

“Anywhere but here,” she also said.

“It’s like a way station,” my dad went on, suggesting a kind of temporary lodging between life and death. “It’s a waiting game.”

“This is it,” my mom added. “There’s no place to go after this.”

“But you have friends here,” I offered, desperate to cheer them up, as if that were my responsibility. Or as if I could actually cheer them up.

“But it’s not like we’re part of a community,” my mom said. “It’s not like when you kids were all young and we were all connected with others through our kids.”

“I really don’t feel a part of anything here,” my dad added. “It’s sad.”

I was dumbstruck. As a family, we hardly ever spoke about our feelings, especially difficult ones. Perhaps, now in their elder years, my mom and dad were willing to open up a bit, be vulnerable. I have to say that I welcomed this change. Yet, it broke my heart to listen to them, members of that renowned “Greatest Generation,” telling me in no uncertain terms how miserable and demoralized they’d become in a place that was supposed to have been the final panacea for their health and happiness, the golden ring at the end of my father’s long, stressful career in business, and long lives for them both.

Those years of happy retirement that my father had been looking forward to most of his working life, which began soon after his honorable discharge from the Marines when WWII ended, was over in what seemed like the blink of an eye. Also, my parents found themselves in a two-bedroom apartment six floors above the ground, where access to the outside world was sealed off but for a small cement slab that was called a “patio” and barely big enough for two or three people to stand. It was the first time since a couple of years after they’d gotten married in 1948 that they did not live in a house of their own. Although we might have moved here and there, at least we had a house we could settle in and, for my father, to feel the gratification of stewardship. The loss of that, no doubt, added to their disorienting tailspin from which, I now believe, my mother and father would never recover.

I’ve come to believe that another reason they felt so discontented and disoriented was because they had deprived themselves of any consistent, physical presence of their grown children and two young grandchildren, who one of my brothers and his wife had brought into the world, simply because by going to Florida they had moved farther away from any of us than ever before. Having retired, they could have lived anywhere, even somewhere close to one of their sons. I would have enjoyed it if had they chosen to live near me, and I even mentioned it to them once or twice. But now they missed us. And needed us. They no longer had any roots in any sort of community nor any consistent physical connections to any of their offspring. And it was killing them.

It was a sorrowful coda to their long and not easy lives. My father died in 2008 at the age of 85. After my father died, my mother moved (again) to another assisted living facility closer to my brother in Colorado to be close to his grandchildren. But she soon became too frail and began to really suffer from dementia, to participate in their lives. She died in 2014 at the age of 87. In part because they had moved so much, in part because many of the friends they’d had from their years in Connecticut and Michigan and Georgia had also moved a lot, and in part because many of these friends had died before my parents did, my brothers and I held no funeral or memorial service for either of them because we didn’t know who among their friends were still around to show up or even how to find them.

“Our obsession with mobility, the urge to move on every few years, stands at odds with the wish to endure in a beloved place, and no place can be worthy of that kind of deep love if we are willing to abandon it on short notice for a few extra dollars,” writes James Howard Kunstler in his excellent 1993 book, The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America’s Man-Made Landscape. “Rather, we choose to live in Noplace, and our dwellings show it. In every corner of the nation we have built places unworthy of love and move on from them without regret. But move on to what? Where is the ultimate destination when every place is Noplace.”

I don’t want to live in Noplace. I’ve been there and I didn’t like it at all. That, along with the moving from one place to the next as I did with my family and on my own later in life may explain why I have not moved from my current home of nearly 26 years.

***

To Weil, having roots and vital connections to the past were necessary ingredients of not just individual lives but also national resilience. It was, according to Weil, precisely the lack of roots and sense of history that led to France’s capitulation to the Germans. She writes:

“The sudden collapse of France in June 1940, which surprised everyone all over the world, simply showed to what extent the country was uprooted. A tree whose roots are almost entirely eaten away falls at the first blow. If France offered a spectacle more painful than that of any other European country, it is because modern civilization with all its toxins was in a more advanced stage there than elsewhere, with the exception of Germany. But in Germany, uprootedness had taken on an aggressive form, whereas in France, it was characterized by inertia and stupor.”

In a nation characterized not so much by inertia and stupor, but by ignorance and inattentiveness, America was ripe to be conned by the COVID-19 psyop that the evil overlords launched against this nation, and against much of Western civilization, in March 2020. So wide and deep was the consequent breach in simple sanity and civil discourse that the deleterious repercussions of the psyop are still with us today on account of, among many things, the intentional evisceration of families and friendships. It feels like a wound that just won’t heal because the bacterial infection hasn’t been eliminated.

To me it is not much of a stretch to think that France’s initial crime of capitulation to the Germans was not very much different than America’s initial crime of capitulation to the COVID-19 psyop. Weil writes: “Just as there are certain culture-beds for certain microscopic animals, certain types of soil for certain plants, so there is a certain part of the soul in everyone and certain ways of thought and action communicated from one person to another which can only exist in a national setting, and disappear when a country is destroyed.”

In The Need for Roots, Weil writes that uprootedness is caused by “military conquest.” She also writes about the effects of the conquerors:

“There is the minimum of uprootedness when the conquerors are migrants who settle down in the conquered country, intermarry with the inhabitants and take root themselves. Such was the case with Hellenes in Greece, the Celts of Gaul and the Moors in Spain. But when the conqueror remains a stranger in the land of which he has taken possession, uprootedness causes an almost moral disease among the subdued population.”

The “stranger in the land,” that Weil writes about were the German occupiers of France. The “stranger in the land” in the COVID-19 coup here in America cannot be reduced to just one enemy you can point a finger at. To be sure, many of the millions of illegal immigrants allowed into the country under the Biden regime can be included among these strangers. But the leaders of the occupation of America are the legion of the unseen, unelected, shadowy deep state commanders in high places. Although long in coming, the COVID-19 coup was both a multi-pronged invasion and infiltration the likes of which America had never seen before and for which most of us were unprepared. And about which most Americans still remain clueless.

Weil was ahead of her time in pointing out that, as Robert Zaretsky, in his book The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas, writes: “For Weil, the act of uprooting is not just physical, but also social and psychological; one can feel uprooted without ever having moved or having been moved.” The massive social and psychological homelessness brought on by the COVID-19 lockdowns dramatically disrupted the human passion for structure and predictability. No longer were we “allowed” to go work and school in the morning; to spend our evenings with friends in restaurants and social events; to travel; to go to church on Sundays; to take a walk in a park; to sit on a beach; to see our aging or ailing family members and friends in hospitals, retirement communities, and nursing homes; and even to attend funerals. All the while, let us recall, liquor stores were allowed to remain open because they were “essential businesses.”

None of this “just happened.” None of this can be attributed to the natural evolution or modernization of a society. None of it was coincidence. All of it was planned. All of it was an invasion designed and carried out to break our will and demoralize us. Because a people without will and without some idea of their individual worth and collective value as a nation—an entire population without roots—are the easiest to control, to conquer, and, ultimately, to kill. Weil writes:

“Uprootedness is by far the most dangerous malady to which human societies are exposed, for it is a self-propagating one. For people who are really uprooted there remain only two possible sorts of behaviour [sic]: either to fall into a spiritual lethargy resembling death, like the majority of slaves in the days of the Roman Empire, or to hurl themselves into some form of activity necessarily designed to uproot, often by the most violent methods, those who are not yet uprooted, or only partly so.”

***

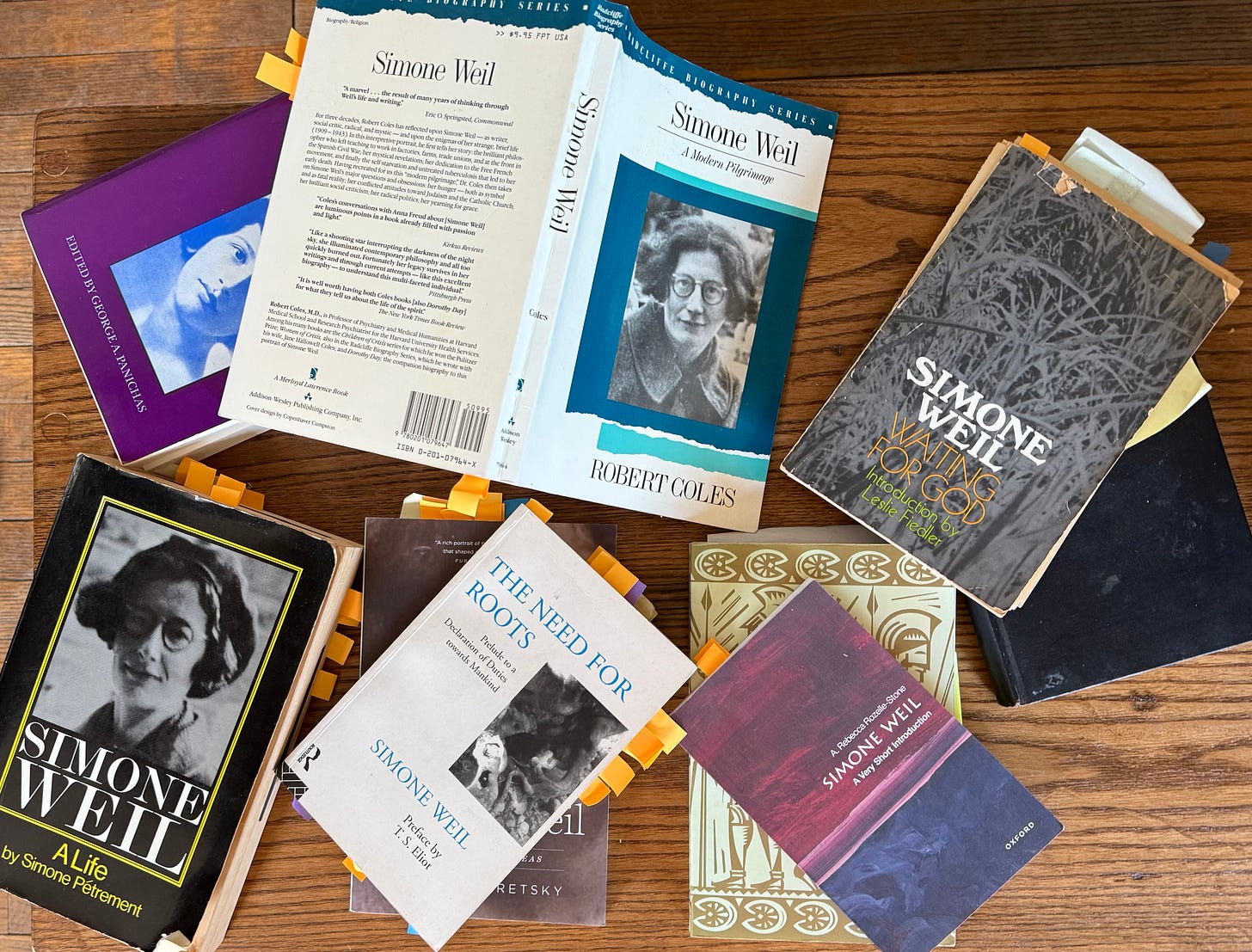

I admired Simone Weil as soon as I started reading her work in the 1980s when I was in my 20s. I don’t recall what initially attracted me to her writing, but I was glad we’d found each other. The first book of hers that I bought and read, Waiting for God, is now falling apart; the glue at the binding is all dried out and the pages are stiff and yellowing. I now have to lay the book on a table and carefully turn each page lest it all fall apart in my hands.

Waiting for God, first published in French in 1949 (under the title Attente de dieu) and later in English in 1952, is a collection of essays and letters that she was writing in her late 20s and early 30s. The letters were to a Dominican priest, Joseph-Marie Perrin, whom she met in 1941 while living in Marseille and writing for the Resistance and just before she and her parents fled to the United States. Perrin had collected the letters and published them under what would become Waiting for God.

Born Jewish but feeling little connection to Judaism, she felt drawn to Christianity even as a child, which she wrote about in Waiting for God. She claimed to have had several mystical experiences. One occurred in Assisi, Italy. Of that experience, she writes in Waiting for God: “There, alone in the little twelfth-century Romanesque chapel of Santa Maria degli Angeli, an incomparable marvel of purity where Saint Francis often used to pray, something stronger than I was compelled me for the first time in my life to go down on my knees.”

Although Weil and I lived years apart, we were close in age by the time she was writing these words and by the time I was reading them. But she was so far above me in the depth of her thoughts and capacity to articulate them that a part of me aspired to know what she knew and to write like she wrote. I would not call it envy; it was, rather, admiration.

What I also admired about Weil then and now is the effort she put into her spiritual journey and into wrestling with her religious conflicts. For much of her adult life she was drawn to Roman Catholicism but never converted. She told Father Perrin that she “never had, even for a moment, the feeling that God wants me to be in the Church.” Weil was also drawn to religious traditions from the east, such as Taoism, Hinduism, and Buddhism. But the main thing that prevented her from officially converting to Catholicism was its unforgivable acts of inhumanity. Cole writes:

“Part of her actively and explicitly disliked the Church for its often dismal history. She was never one to forget, and not easily able to forgive, her faults or those of institutions, especially the mighty ones. Though she knew Christ forgave the poor and the humble, to forgive the Church its lone and sometimes sordid history (the Inquisition, the debauched papacy of the Middle Ages) was more than she could bring herself to do after years of careful study and contemplation.”

In Simone Weil: A Very Short Introduction by A. Rebecca Rozelle-Stone, we read:

“Weil realized that her vocation, which was a calling to be intellectually honest to the highest degree, necessitated that she remain outside the Catholic Church and detached from its dogmas. The Church’s powerful spirit of collectivism, its historical abuses committed against the vulnerable in the name of salvation, its exclusion of diverse peoples and cultures, and the blind acceptance of doctrine would compromise the integrity of her search for truth. Thus, Weil refused to become part of the official organization to partake in its sacred rites, like baptism or the Eucharist.”

Finally, what I also admire about Weil then and now was her untiring and intense fascination in life itself. She threw herself wholeheartedly into everything that interested her—and against what riled her. And one of the things that riled her the most was the topic of colonization, and she wrote about the injustices and hypocrisy of French colonial policies and, for that matter, all colonization, coming to the conclusion in 1943 that any sort of colonization by any nation over another was the source of all the misfortunes that plagued the entire world.

“France was not merely occupied by the Germans; instead, it had been colonized by them,” Zaretsky writes. “It was the act of colonization that the Resistance movements sought to end.” Weil herself writes of WWI: “The harm that Germany would have done to Europe if Britain had not prevented German victory is the harm that colonization does, in that it uproots people. It would have deprived people of their past. The loss of the past is the descent into colonial enslavement.”

As Germany had once again invaded France during WWII, Zaretsky writes: “The dynamic between a totalitarian Germany and a republican France was, for Weil, identical to the dynamic between an imperial France and its imperial subjects. Just as France, along with the rest of Europe, risked material and spiritual annihilation at the hands of the Nazi overlords, so too did the colonized in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific face the same fate at the hands of their French overlords.”

I bring this up because it got me thinking. Reflecting on Weil’s thoughts about colonization in light of the most recent high crimes against humanity that we’ve endured, I wonder about the possibility that Western civilization, including America this time, was not just a victim of an invasion by the evil ones with their COVID-19 psyop and everything that followed; it was also a colonization. And not just any sort of colonization.

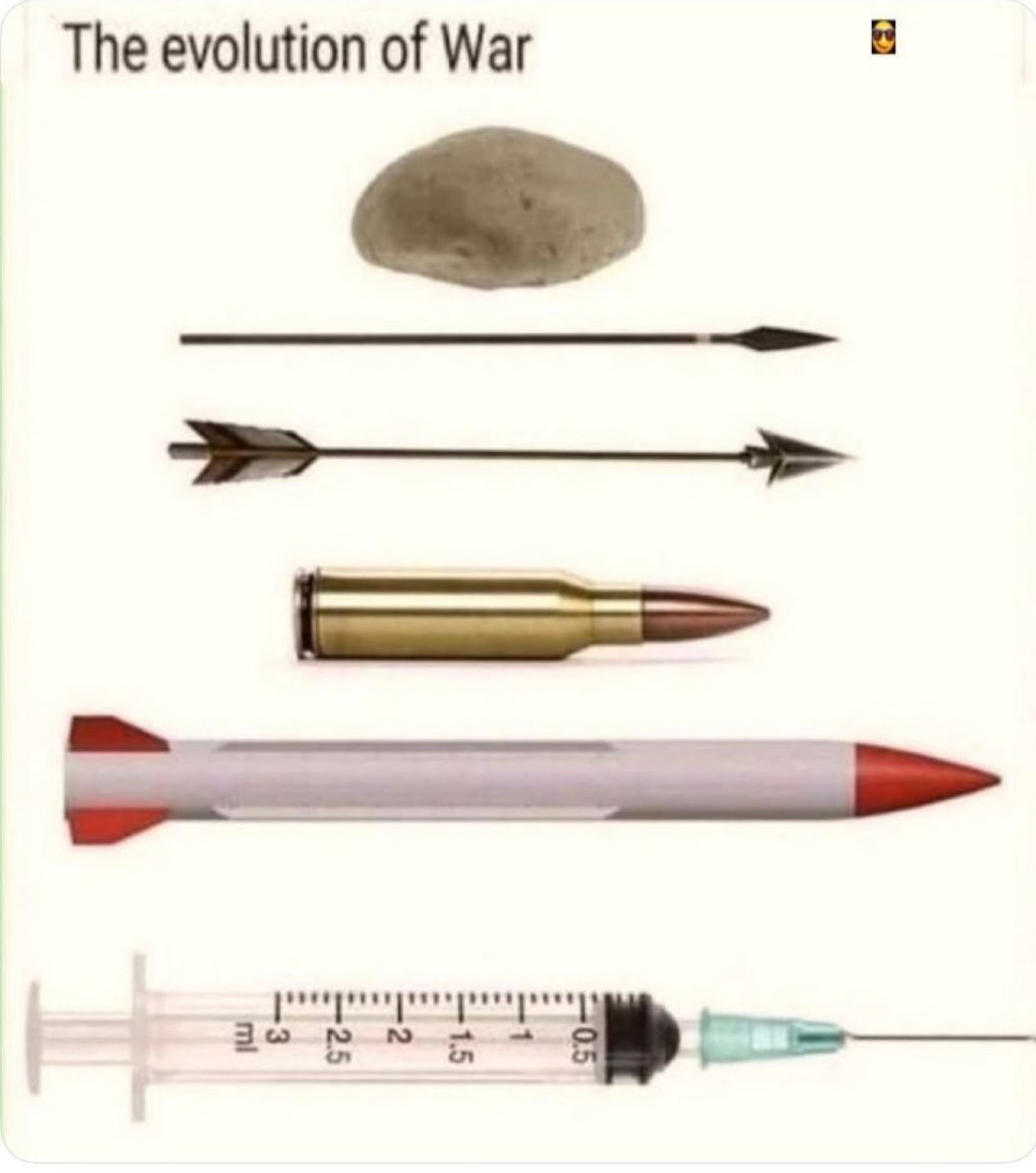

A meme a friend recently texted me depicts the evolution of war with simple illustrations of the weapons used throughout time. The first weapon is a stone. The next weapon is a spear, then an arrow, then a bullet, then a missile. The final weapon is a syringe. And in this war, I am haunted by the idea that it’s not just nations being invaded and colonized, but also our bodies with a bioweapon that was injected into billions of people around the world, a bioweapon that has injured and killed millions, a bioweapon that contains nanoparticle technology that might usher in a transhumanist mind-control nightmare.

***

Weil never completed her long and ambitious treatise for the Free France organization in London—The Need for Roots—because of her failing health. In April of 1943, ailing from tuberculosis and eating far less than what the doctors treating her recommended—she insisted that her food be sent to French prisoners of war—and with the war still raging on the other side of the English Channel in France and elsewhere in Europe, she was admitted to a hospital in London.

But it was not her health that she was most concerned about now, if ever. It was her legacy. “What preoccupied her during these days when she felt her chances for living rapidly waning was the thought of the truths she had spoken and which it seemed to her had not been heard, and perhaps never would be,” Pétrement writes. “She was very pessimistic about this. In one of her July letters she implies that nobody pays attention to her ideas.”

On August 17, she was rushed by ambulance to a sanitorium in Ashford Kent, some 60 miles by road southeast of central London. And this is where she died on August 29 at the young age of 34 from complications due to tuberculosis and anorexia.

Weil was always hard on herself in so many ways. She admits in Waiting for God: “I have extreme standards for intellectual honesty, so severe that I never met anyone who did not seem to fall short in it in more than one respect; and I am always afraid of failing in it myself.” She also felt all her life that she could never do enough for others. And it is perhaps on account of this that she gave her life away.

There is some debate among historians if Weil, by starving herself, might have committed suicide. We read in Pétrement’s biography: “The coroner issued a verdict of suicide. The death certificate indicates that the cause of death was ‘cardial failure due to myocardial degeneration of the heart muscles due to starvation and pulmonary tuberculosis’; to which was added the following: ‘The deceased did kill and slay herself by refusing to eat whilst the balance of her mind was disturbed.”

Weil never made it back to her beloved France. She was buried on August 30 in the Catholic section of what was then Ashford’s New Cemetery (now named Bybrook cemetery) and now, according to the Google maps I looked up online, is sandwiched between a cinema complex and apartment buildings. Seven people attended the funeral, Pétrement writes, adding: “A priest had been asked to come; he took the wrong train or missed his train and never arrived.” Weil’s parents and her brother, still in the United States and having little knowledge of Simone’s condition, learned of her death by cable sent by one of Simone’s friends. Simone Weil’s grave is marked by a flat stone, as if those who laid the stone had fulfilled what may have been her final wish to draw as little attention to herself as possible.

Weil’s parents returned to France after the war, but her brother remained in the United States. After a teaching career in America and Brazil, he landed at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., where he would spend the remainder of his career. He died in 1998 at the age of 92. Their father, Bernard Weil died in 1955 at the age of 83. Her mother, Salomea “Selma” Reinherz, died in 1965 at the age of 84.

***

The war against individual sovereignty and collective freedom is old and new for it is ongoing. And what’s required to vanquish the ever-present overlords is an individual and collective effort, against all odds, to defeat them. As Weil observes The Need for Roots:

“The French people, in June and July, 1940, were not a people waylaid by a band of ruffians, whose country was suddenly snatched from them. They are a people who opened their hands and allowed their country to fall to the ground. Later on—but after all long interval—they spent themselves in ever more and more desperate efforts to pick it up again; but someone had placed his foot on it.

“Now a national sense had returned. The words ‘to die for France’ have again taken on a meaning they hadn’t possessed since 1918.”

So, too, here in America. And it would seem that now’s a good time for each of us to somehow plant or strengthen all those roots that Weil writes about—and that we all need so much. “In the atmosphere of anguish, confusion, solitude, uprootedness in which the French find themselves,” Weil writes of France during the German occupation, “all loyalties, all attachments are worth preserving like treasures of infinite value and rarity, worth tending like the most delicate plants.”

Post Script

Albert Camus, like Simone Weil, had distanced himself from communism as well as from Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. Although Camus and Weil had never met one another, Camus had published some of her work in a journal he was working for and he admired The Need for Roots, which he presented in a monthly listing of new titles in another journal he was working for. Weil had been dead 14 years by the time Camus won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957, but he admired her so much that the day before he flew to Sweden to receive the prize, he went to her childhood home to visit her mother and to request a photo of Simone to take with him to Stockholm. Camus himself also died young, killed in a car crash in January 1960 when he was 47.

Selected Bibliography

Coles, Robert. Simone Weil: A Modern Pilgrimage. Reading, Massachusetts. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1987.

Kunstler, James Howard. The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America’s Man-Made Landscape. New York, N.Y. Touchstone, 1993.

Panichas, George A., ed. The Simone Weil Reader. Mt. Kisco, N.Y. Moyer Bell Limited, 1977.

Rozelle-Stone, A. Rebecca. Simone Weil: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford, United Kingdom. Oxford University Press, 2024.

Weil, Simone. The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties towards Mankind. Translated from the French by A.F. Wills. New York, N.Y. Routledge, 1978.

Weil, Simone. Waiting for God. Translated from the French by Emma Craufurd. New York, N.Y. Harper & Row, Publishers, 1951.

West, Diana. American Betrayal: The Secret Assault on Our Nation’s Character. New York, N.Y. St. Martin’s Press, 2013.

Zaretsky, Robert. The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas. Chicago, Ill. The University of Chicago Press, 2021.

Don’t want to subscribe? You can leave a one-time tip for as little as $5. Every little bit helps me pay the bills so I can continue to offer you thoughtful insights into today’s world combined with the written wisdom of those who have come before us and who have helped guide us on our search for truth, freedom, and beauty. I would love to hear from you. Feel free to email me at jimkullander@gmail.com

I applaud the way you continue to process the mass formation psychosis, Jim, because I also am never going to recover from the shock and awe of what went down in March 2020. Today I saw dozens of people about town wearing face masks still. Simone Weil described France as a nation mostly populated by malleable beings without a compass. They were ripe to be picked, squashed, booted, beaten and conquered. I watched in disbelief as America bent over, kneeled down and submitted to "the science" and to TV and shunned all critical thinking. It was a willing mass suicide. How your dad devoted his life to the financial grindstone and died bereft and displaced, of his pursuit for more money, was a slow suicide. My family, friends and neighbors have shown they will abandon all quality of life in an instant when told to, then obediently be injected with poison and the Big Lie that led them there, and that's proven to be suicide also.

Your peace and sanity is within, that's where your home has always been. This changeful world is an unrelenting machine working on awareness and delivering the perfect medicine to guide you home. It's all perfect. If sometimes it seems everything is fucked up, understand that it is perfectly fucked up. There's some cosmic humor for you. Stay in the beautiful Hudson Valley and I'll stay out here in northern New Mexico and we'll continue observing endlessly because that's all we can do.

Mr. kullander. Reading your article reminded me of this quote. referring to a review of Arvo Part’s Tabula rasa. “what kind of music is this? whoever wrote it must have left himself behind at one point to dig the piano notes out of the earth and gather the artificial harmonics of the violins from heaven…..Wolfgang Sandler

You do so well digging deep into soul and spirit. Thank you for sharing this incredible woman. and your own history .