The Captive Mind

A Meditation on a Book by Czeslaw Milosz

“Eyes that have seen should not be shut; hands that have touched should not forget when they take up a pen.” – Czeslaw Milosz, The Captive Mind

I could see out the train window that we were leaving the Soviet Union. There were no signs that said “Leaving the Soviet Union” or “Entering Finland.” But what I did see was clear enough: a tall, barbed wire fence, on the other side of which was a wide swath of closely cropped meadow, then another tall, barbed wire fence.

We were on a train for the short trip from Leningrad (now called Saint Petersburg) to Helsinki. And what I was looking at was the border between the Soviet Union and Finland. The idea was that if you wanted to escape and miraculously managed to scale the first fence, you might be seen running across the meadow—or the footprints you’d leave behind would be seen—and if you made it over the second fence, you’d eventually be hunted down in the thick conifer forest that straddled both countries, and be dragged back and locked up. I had learned all this from a man in Leningrad who, a few years before, had tried to escape and ended up in prison.

We—my then wife and myself—were nearing the end of a year and half of living, working, and traveling in the world’s few remaining communist countries. We had been teachers of English as a second language at a university in Beijing from February 1986 until June 1987. For our return to the United States, we had decided that, instead of hopping on a plane and flying back east across the Pacific Ocean, we’d go by train north through China, Mongolia, then west through the Soviet Union, then to Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and finally to Holland, where we’d catch a cheap flight from Amsterdam to New York City. At the end of this trip, we would have circled the globe. Not only that; I would return a completely changed man from the time I’d left the United States a year and a half before.

We departed from Beijing on a sunny, hot afternoon in August for the five-day, Trans-Siberian Railway journey to Moscow. We were travelling with two American teaching colleagues in a compartment with four berths. One of our colleagues spoke Russian. And with him and a driver we had to hire—back then before the fall of the Soviet Union foreign tourists were not allowed to wander around on their own—we toured Moscow and a few surrounding towns before we went our separate ways. My wife and I took a train north to Leningrad, where we pinched from the sparse but free hotel breakfasts enough scraps of fatty cold cuts, limp slices of cheese, and a hunk of bread to last us to the next morning. We were quickly going broke outside of China and needed to make sure we had enough money in traveler’s checks to last us until we got to Amsterdam and our flight home.

We were also growing bone tired. Life in China had been rough. One of the things I remember most was how everyone was still picking through the physical and emotional ruins of some forty years of Maoist carnage in which upwards of 80 million souls were executed or starved to death or killed themselves. We lived and worked among the survivors and became unwitting witnesses to tales of brutality and butchery depicting the horrors that a dictatorship can rain down on a country and its people. That in itself wore us down as so many of our students confided in us what life was like for themselves and their families under Mao. For most of them, it was the first time they’d been able to talk to a foreigner about this, and they struggled with their broken English and with their traumatic memories. Time and again they would say to us, “You cannot imagine….” I would agree; no, I couldn’t.

Now, our train slowed to a crawl and continued like that for miles. Then it stopped nowhere near any buildings. Suddenly we saw armed Soviet soldiers outside, looking under the train cars. German shepherds straining on their leashes crawled under the cars. Searching for people trying to escape, I figured. We were in a compartment of four seats. I don’t recall the nationalities of the other two passengers but they were not American. We looked at each other and shrugged our shoulders and sat in silence waiting for the train to start moving again. Presently, we heard the thumps of heavy boots come down the aisle of the train. We heard compartment doors slide open. We heard muffled voices. It sounded as if passengers were being questioned and having their luggage searched. Then we heard the doors slide shut again.

As the sounds came closer, I panicked. I remembered that in my suitcase I had copious, scathing journal entries of our time in China. I had photos of people and places that maybe I should not have had. I had some Chinese renminbi and some Soviet rubles and kopecks. I had a Chinese flag. And I had a Russian flag that I had scored in a trade with the man in Leningrad who had tried to escape. We’d given him and his wife some of our American clothes in exchange. Had they been KGB spies who’d tricked us? Were we in trouble now?

Our compartment door rolled opened. A soldier filled up the doorway. He questioned us while he reviewed our passports and looked around. Where had we come from? Where were we going? How long had we been in the Soviet Union? What did we do? Who did we talk to? He spotted our bags above us on the rack. He wanted to know what was in them. Some clothes, some books, and some photos, I said, playing it cool. I wondered: Was he going to open our bags? What would happen if he found the flags? Is it even legal to take a Chinese flag or a Russian flag out of the country? And what about the Chinese and Soviet money? I had no idea. I was frozen by the thought that we had done something wrong, that we would be hauled off the train, hustled into some military vehicle, and thrown in jail. Such is the nature of a mind battered by a totalitarian regime. Perpetual paranoia.

The soldier slid the door closed and soon the train started moving again. Silently relieved, I sat back in my seat and gazed out the window into the shadows and the sunlight of the endless forest. After a few more minutes the train stopped again. Now we were at some sort of station. All I could see were warehouses and other track lines. Then, again, I heard heavy footfalls come down the aisle, the sound of compartment doors sliding open, voices. As the sound drew closer to us, I grew frightened again. Were we still in the Soviet Union? What was going on? Then our compartment door flung open. A tall, thin man with a tanned face, a big smile, and brilliantly white teeth and dressed in a bright blue uniform and cap poked his head in and, with a flourish, said, “Welcome to Finland!”

At that moment everything changed inside and all around me. I can’t remember what I said but I’ll remember forever how I felt: ecstatic. Almost dizzy with relief and joy, so inexpressible yet so simple. An intense and perfect happiness and inner peace. I might have laughed; I was so giddy. Freedom, that’s what it was. After a year and a half of watching what I said and who I talked to, I could now say whatever I wanted to whomever I wanted. I felt no one could search my bags, take my journals, and haul me off to be locked up for something I had that the government did not want me to have. I felt I could write what I wanted to write and about anything I wanted to write. I think the feeling was so startling because it was so unexpected. All of this welled up in me in a matter of seconds, like Scrooge waking from his nightmare with the dreadful Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come and realizing it was all just a dream.

Our sliding door remained open this time and outside on the other side I saw a cafe. We got off the train for a short break. Finland greeted us with all its Nordic splendor. The air was cool, the sky deep blue, the sun brilliant, the clouds big and fluffy. We went into the café, the first in the free world we’d seen in a year and a half. I was awestruck. It was like I’d never seen anything like this before. I saw on a countertop a basket of oranges the size of softballs, a far cry from the shriveled lumps I’d seen just over the border. I saw sandwiches of all sorts made from huge loaves of bread and thick slices of meat and cheese. I saw boxes of crackers and cookies and jars of jams and cellophane bags of candy all neatly lined up on the shelves. And all the time I was thinking that no one just over the border in the Soviet Union or way back in China could touch me now. That was the best feeling of all. It was behind me. It was over.

I bought a cup of coffee, a sandwich, and some oranges. I didn’t even ask what anything cost because I didn’t care. I wanted to buy everything, broke as we were. No, I just wanted to look. It was a feast for the mind hungry for simple beauty and abundance, for the long-starving soul. I was so exhilarated that I wanted to hug the heavyset woman at the cash register. At a small table we ate our sandwiches and an orange and I sipped my coffee as, remarkably, Aaron Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man floated softly through the air. I could have cried a river from relief and happiness. But that was not all. I also felt sad for leaving all my desperate students back in China, some of whom had become my friends. I even felt sad for the couple who had traded us a Russian flag for some clothes off our backs, and who, as we were parting at the Leningrad train station, complained bitterly, “Why is it that you can go anywhere you want and we can’t? It’s not fair. It’s not right.”

That memory haunts me still.

But another, happier memory, has stayed with me, too. We strolled outside to get back on the train to Helsinki. I saw a sign of the station name: Vainikkala. I looked past the sign and down the tracks toward the direction from which we’d just come, toward the vast Soviet Union looming like a forbidden planet out there in the woods. So near yet so far. I was still lost in a daze of complex emotions, thinking about how far we’d come and so grateful we’d made it to where we now stood, when an American woman we’d seen in the café brushed past us and breathlessly said, “I don’t want the train to leave without me.” I turned to my wife and said, “The train can leave without me. I’m in no hurry to go anywhere now. The train could leave me here and that would be just fine.”

***

I started reading The Captive Mind by Czeslaw Milosz just before the most recent U.S. Presidential election and finished it a few days after. The book is about what life was like in Poland during the Nazi occupation and then, a few years later, under communism, which lasted there into the early 1990s. The final evacuation of Soviet troops from the country didn’t happen until 1992. In the book, Milosz writes that he seeks to “create afresh the stages by which the mind gives way to compulsion from without.” The bulk of the book contains profiles of Polish writers and poets Milosz knew and who had given themselves over to the Marxist call of the historical necessity of dialectics and the socialist realism of art and literature—what Milosz calls the “New Faith”—in which a communist system is rooted and on which it struggles to live.

It struggles to live because Marxism is not naturally productive of anything but misery and death. It feeds on people and on both their humanitarian and selfish selves like an enormous leech. It will eventually suck the life out of not only those who live to defeat it but also those who live to sustain it. It is a form of governance in which no one but the puppet masters pulling the strings wins and everybody else loses. Milosz writes: “For the intellectual, the New Faith is a candle that he circles like a moth. In the end, he throws himself into the flame for the glory of mankind.”

I know how these mechanisms work and not just by reading about it in books like The Captive Mind. I also lived it. And not just in China and the Soviet Union. All of us have been living shades of it here in the United States for nearly five years now. But only a few of us have been aware of what has really been going on both here in America and in much of the rest of the free world. Aware that the so-called pandemic had nothing to do with protecting our health and well-being. On the contrary, it had been an orchestrated assault to destroy us and the free world no less than a Marxist takeover as so many got swept up in the propaganda—a kind of New Faith 2.0—that led to the lockdowns, the closures, the social distancing, the censorship, and, ultimately, the mandated mass injections of a bioweapon malevolently promoted for that “glory of mankind” but which thus far has killed millions and injured and crippled many more. Because of what I’d seen in China and the Soviet Union, I recognized the degradation and humiliation of the individual human spirit in exchange for that high and mighty, forced and fabricated, collectivist “glory of mankind” in the government’s commands of “do it for others” and “stop the spread” happening here. I saw the manipulative horrors depicted in The Captive Mind imposed here with my own eyes.

Like Milosz’s writer friends who became zealous indoctrinated adherents to this “New Faith,” millions of Americans got swept up in the frenzy of covidmania. And our world—like the world of Milosz—became divided. Seeking to understand why he eventually left Poland—which he did reluctantly—he reflects on his relationship with one of his writer friends who’d given himself over to the State. He writes about one friend: “Should I renounce what is probably the sole duty of a poet only in order to make sure that my verse would be printed in an anthology edited by the State Publishing House? My friend accepts naked terror, whatever name he may choose to give it. We have parted ways.”

Much the same has happened here. Many of us have, indeed, parted ways. And many of us, who have a good idea of what’s really been happening to us, who will not accept the “naked terror” of the government’s campaign of fear mongering, have had to become actors, like many people did in Poland under communism. Here, many of us have had to pretend that everything that was happening was good for humanity, that all those diktats were enforced to contain a virus that we knew was no more lethal to normally healthy people than the common flu. We’ve had to pretend that the so-called vaccine really was, and remains, “safe and effective.” That it saved millions of lives.

Among friends, family, and colleagues, many of us have had to pretend that nothing seriously awry happened or is happening. We still dare not speak the truth for fear of being “canceled” or brutally turned upon, dismissed as tin-foil hat wearing conspiracy theorists. We tried. And we failed. It hasn’t been easy. Because what we know is not some innocent, white lie. We’ve had to pretend that it was only natural that millions of people had been maimed or killed by the jabs, including friends and family members. Mysterious—so many young and healthy people keeling over from myocarditis or aneurysms or getting a virulent, fast-spreading cancer—but natural. “People die,” my girlfriend’s brother scolded her when she questioned the strange, sudden death of a vaxxed, healthy, 39-year-old clean-living nephew while he was running on a treadmill. It feels as if we’ve had to pretend—after screaming into the wind and unsuccessfully waking up friends and family and colleagues—that another Holocaust was not happening while we watched people being loaded up in trains that we knew were bound for a new type of Auschwitz. Talk about a nightmare.

***

Fresh from that frying pan of covidmania, we then had to deal with the Trump Derangement Syndrome fire. My awakened friends and I—former liberals turned conservatives—dared not reveal among our many still (and in some cases, vicious) liberal friends who we were going to vote for. I dared not put any lawn signs in my yard or bumper stickers on my car because I did not want my house torched or my car vandalized by the woke mafia or by some rogue freak having an apocalyptic fit. I did not want to be further spurned by some of my neighbors who had already shunned me because I would not join their covidmania cult. Even after the election we continued to feel it best to keep our voting preferences to ourselves here behind enemy lines in New York’s Hudson Valley lest we find ourselves on the wrong end of the firehose of wrath and contempt that we saw unfolding in real time on Facebook, X, and TikTok.

The outrage, vitriol, and insanity spooked me. It almost seemed like a kind of demonic possession. Something had gone terribly wrong, I thought. Not with the election—like it did in 2020—but with those who were completely unhinged by the results. This is what happens, I thought, with Milosz’s captive mind. The left-leaning legacy media had whipped millions into a rage with their relentless attacks against Trump and of anyone who supported him. What’s more, these victims of propaganda were expressing fear for their very lives and the lives of their children, especially their daughters. (Never mind the scourge of child trafficking infiltrating our borders that has been allowed to happen under President Joe Biden and about which Vice President Kamala Harris during her ultimately failed presidential campaign never spoke of ending.) Many sought out each other for emotional support and to strategize about how to “survive” the next four years. Many posted about leaving the country. (Buh-bye.) One Buddhist publication I follow on Facebook posted an article alluding to the Trump victory titled: “4 Ways to Curb a Panic Attack with Mindfulness.” There was a photo of one Starbucks employee laying a comforting hand on the shoulder of another employee slumped on the floor with a caption that read: “Starbucks is feeling it today.” (Guess I won’t be going back there any time soon.)

Religious and spiritual leaders I once admired joined in the flummoxed lamentations. The legacy media, too, raised their grating voices in a chorus of alarmists and complainers. In a November 7 New York Times piece titled “Devastated Democrats Play the Blame Game, and Stare at a Dark Future” you can read: “Many Democrats were considering how to navigate a dark future, with the party unable to stop Mr. Trump from carrying out a right-wing transformation of American government. Others turned inward, searching for why the nation rejected them.” In an essay titled “Trump 2.0: Here Comes the Night,” the New Republic wails: “We are headed into uncharted territory as a people and a nation. Trump and his allies have promised to initiate their radical right-wing agenda the minute after he takes his hand off the Bible on Inauguration Day. We are about to experience an unprecedented assault on the Constitution and our civil liberties related to speech and assembly, and an abandonment of norms related to the military, the Justice Department, and government contracting that will make the first term look, well, normal.”

Apparently, Trump’s opponents are so sure about the imminent end of democracy with his presidential victory because they are the ones who are going to end it.

I remember a Tucker Carlson interview in October with the journalist Mark Halperin, who at one point said that a victory by Trump will bring “the greatest mental health crisis in the history of the country.” I did not doubt him. And he was right. What I’ve seen made me think of the daily “Two Minutes of Hate” depicted in George Orwell’s 1949 dystopian novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four during which the citizens of Oceania had to watch a film depicting Emmanuel Goldstein, the principal enemy of the state, and then loudly voice their hatred for this enemy and then their love for Big Brother. Orwell writes: “The horrible thing about the Two Minutes Hate was not that one was obliged to act a part, but that it was impossible to avoid joining in. Within thirty seconds any pretense was always unnecessary. A hideous ecstasy of fear and vindictiveness, a desire to kill, to torture, to smash faces in with a sledge hammer, seemed to flow through the whole group of people like an electric current, turning one even against one’s will into a grimacing, screaming lunatic.”

We Trump supporters can collectively say: “Je suis Emmanuel Goldstein.”

This contempt also made me think of something I was reading about in The Captive Mind. It is a passage about hatred finding a purpose. It made me wonder if this is what I saw happening among the unhinged leftists and the shills in the media. They all now had a target for their free-floating hatred, like the citizens of Oceania in Orwell’s novel. In a profile of a writer being recruited by Poland’s communists, Milosz writes:

“He was young and needed educating, yet he had in him the makings of a real Communist writer. Observing him carefully, the Party discovered in him a rare and precious treasure: true hatred…. His hatred was like a torrential river uselessly rushing ahead. What could be simpler than to set it to turning the Party’s gristmills. What a relief: useful hatred, hatred put to the service of society!”

But later this writer whose hate was honed to attack others eventually hated himself. The writer, Tadeusz Borowski, whom Milosz referred to in his book as Beta, was arrested in 1943 by the Gestapo and imprisoned in Auschwitz. After the war, Borowski became a propagandist for the ruling Communist Party. Eventually, however, he became disillusioned and fell into a debilitating depression and ultimately took his own life. The chapter about him in Milosz’s book is called “Beta, The Disappointed Lover.” Milosz writes:

“He was found one morning in his home in Warsaw. The gas jet was turned on. Those who observed him in the last months of his feverish activity were of the opinion that the discrepancy between what he said in his public statements and what his quick mind could perceive was increasing daily.”

A moth drawn to the flame.

The morning after Election Day, November 6, recalled for me some of the exaltation I’d felt long ago when that train delivered us from the Soviet Union into Finland—and the free world beyond. I felt that as a nation we were now going to put behind us a president and a presidential administration that for the past four years has been shredding the roots of American history, culture, and the inalienable rights to life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness. To me, there is nothing dark at all about this future. When a new love, or an old love that had soured, suddenly rallies and turns to you and says, “I think we’ve turned a corner”—that’s what this new day feels like to me.

For all its faults, I love this country just as I love those closest to me despite their faults. I am old enough and wise enough to know that neither Trump nor his administration are going to make all our troubles go away. Already, his cabinet picks have some unsavory, jab-pushers among them, including Janette Nesheiwat, Mehmet Oz, Marco Rubio, Tulsi Gabbard. Not to mention Trump himself, who has still not walked back his claim that Operation Warp Speed, which he claims to have put in motion, saved hundreds of millions of lives. But I do believe, as the wisdom of the ages proclaims, “The fish rots from the head down.” Biden and his administration are truly one massive, stinking, rotten fish.

***

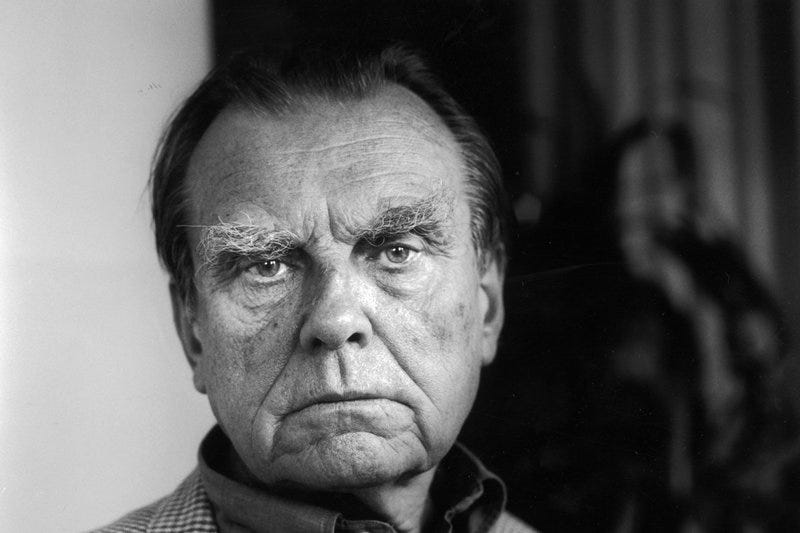

Czeslaw Milosz, (pronounced CHESS-wahf MEE-wosh) lived through a tumultuous time in European history. He was born in 1911 into a Polish-speaking family in Szetejnie, Lithuania, which along with Poland, Latvia, and Estonia were part of the then Russian empire. His parents had moved to Lithuania to temporarily escape the political upheaval in their native Poland. He was only three when World War I broke out.

After World War I, the family returned to their hometown where Milosz attended local Catholic schools. He attended high school in the city of Vilnius and enrolled in law school at the University of Vilnius, graduating at the age of 23. He was working in Warsaw for Polish Radio when the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939, after which he joined the Polish underground and worked as a writer and editor of anti-Nazi publications.

After World War II, Milosz became a member of the new Polish communist government’s diplomatic service and was stationed in Paris, France, as a cultural attaché. There, he befriended Albert Camus, one of the few French intellectuals to offer friendship and support, according to Milosz: A Biography, by Andrzej Franaszek. Others regarded Milosz as “something of a leper or a sinner” for his opposition to “the future.” This future, according to other French intellectuals at the time, was communism, which Camus also opposed.

Had he returned to Poland then, Milosz might have lost his life. A skeptic of Marxist rule and not a party member, he was tipped off that, if he returned, he faced arrest and trial in the Stalinist purges then under way in Poland. In 1951, he left his post and took political asylum in France. After his defection, Milosz remained in Paris, where he worked as a translator and freelance writer. In 1960, he accepted a teaching position at the University of California, Berkeley, and became an American citizen in 1970. Highly regarded for his poetry in Poland, he was still years away from the international notoriety that he would earn in 1980 when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

If Milosz were alive today, I wonder what he would have done these past five years. I wonder if he would have seen through this modern, secular Western culture charade in which millions of people have given themselves over to propaganda, indoctrination, and consequent outrage, and called it out. I do know what he did in Poland under communist rule. Just like many of us now, he, too, had to pretend. In communist Poland, Milosz writes:

“Officially, contradictions do not exist in the minds of the citizens in the people’s democracies. Nobody dares to reveal them publicly. And yet the question of how to deal with them is posed in real life. More than others, the members of the intellectual elite are aware of this problem. They solve it by becoming actors.” With this sort of acting, he goes on, “one does not perform on a theater stage but in the street, office, factory, meeting hall, or even the room one lives in.”

Surrounded by the misguided leftists in academia and literary circles all around the world in which he had operated, would he have pretended to know nothing of the lies our government was telling us? Would he have joined the jabfest? Or would he have had the good sense to refuse the mandates and then, as a result, be kicked out of his job? But where would he flee? Who would publish him today? Would he have started a Substack column? Would he be considered “something of a leper or a sinner” like he and others had been in 1950s France? For America has become the sort of nation he’d fled. As James Howard Kunstler points out in a recent column: “Mr. Putin must marvel at how much America under ‘Joe Biden’ is loving the old Soviet Union—since we’re doing everything possible to emulate its workings. We’ve got censorship. We’ve got an FBI-turned-KGB swatting citizens guilty of nothing and a DOJ stuffing them in our gulag. We’ve got a senile president every bit as non compos mentis as Konstantin Chernenko was. We’ve neatly managed to bankrupt ourselves.”

Would Milosz even have been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature today? Poland was still suffering under communist rule when he expressed what many of us are feeling today about the lies and censorship we’re suffering at the hands of our government. In his Nobel lecture, where he speaks of the destruction of friendship between nations, I think of the destruction of friendships between people. He said:

“Crimes against human rights, never confessed and never publicly denounced, are a poison which destroys the possibility of a friendship between nations. Anthologies of Polish poetry publish poems of my late friends—Wladyslaw Sebyla and Lech Piwowar, and give the date of their deaths: 1940. It is absurd not to be able to write how they perished, though everybody in Poland knows the truth: they shared the fate of several thousand Polish officers disarmed and interned by the then accomplices of Hitler, and they repose in a mass grave. And should not the young generations of the West, if they study history at all, hear about the 200,000 people killed in 1944 in Warsaw, a city sentenced to annihilation by those two accomplices?”

***

The Captive Mind was published in 1953. It was his first collection of essays. And it was this book, and not his poetry, that first brought Milosz’s name to the attention of American intellectuals, writes Franaszek in his biography. The Captive Mind was compared to Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon and Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. This was not what Milosz had expected or even wanted. First off, because the book was somehow considered “crypto-communist,” it delayed for nine years his chances of getting a visa to America. Also, the book earned him a bad name among certain Poles both here in America and at home in Poland. He said in an interview with the Partisan Review and quoted in Franaszek’s biography, that he was considered a traitor among the progressives. But what he liked least of all on account of the book was that “I was considered a prose writer, a scholar in the field of political science.”

In the book he explains his reasons for defecting, which, as I noted above, he did reluctantly. Milosz writes: “I lived through five years of Nazi occupation. Today, looking back, I do not regret those years in Warsaw, which was, I believe, the most agonizing spot in the whole of terrorized Europe. Had I then chosen immigration, my life would certainly have followed a very different course. But my knowledge of the crimes which Europe has witnessed in the twentieth century would be less direct, less than it is.”

A few pages later he offers a deeper explanation:

“My mother tongue, work in my mother tongue, is for me the most important thing in life. And my country, where what I wrote could be printed and could reach the public, lay within the Eastern Empire. My aim and purpose was to keep alive freedom of thought in my own special field; I sought in full knowledge and conscience to subordinate my conduct to the fulfillment of that aim. I served abroad because I was thus relieved from direct pressure and, in the material which I was sent to my publishers, could be bolder than my colleagues at home. I did not want to become an émigré and so give up all chance of taking a hand in what was going on in my own country. The time was to come when I should be forced to admit myself defeated.”

One of the things that struck me about his aversion to Marxism was that it was not only emotional; it was also physical. He writes:

“The actual moment of my decision to break with the Eastern bloc could be understood, from the psychological point of view, in more ways than one. From the outside, it is easy to think of such a decision as an elementary consequence of one’s hatred of tyranny. But in fact, it may spring from a number of motives, not all of them equally high-minded. My own decision processed, not from the functioning of the reasoning mind, but from a revolt of the stomach. A man may persuade himself, by the most logical reasoning that he will greatly benefit his health by swallowing live frogs; and, thus, rationally convinced, he may swallow a first frog, then a second; but at the third his stomach will revolt. In the same way, the growing influence of the doctrine on my way of thinking came up against the resistance of my whole nature.”

In so many words, Milosz found tyranny evil. And evil is revolting. M. Scott Peck, in his 1983 book, The People of the Lie, writes: “The feeling that a healthy person often experiences in a relationship with an evil one is revulsion…. Revulsion is a powerful emotion that causes us to immediately want to avoid, to escape, the revolting presence…. Evil is revolting because it is dangerous. It will contaminate or otherwise destroy a person who remains too long in its presence.” Evil, Peck writes, is also confusing. As Milosz affirms about Marxism: “A man’s subconscious or not-quite-conscious life is richer than his vocabulary. His opposition to this new philosophy of life is much like a toothache. Not only can he not express the pain in words, but he cannot even tell you which tooth is aching.”

Before he finally and grudgingly defected, Milosz had become a local eyewitness to the rise and fall of the fascistic and communist empires that at the time were attempting to conquer the world. And humanity is all the better for it. For he gave the world a vast compendium of literature attesting to what he saw and touched and thus would write in The Captive Mind the line I quoted above: “Eyes that have seen should not be shut; hands that have touched should not forget when they take up a pen.”

Milosz closes The Captive Mind with an imaginary meeting at the hour of his death with the Greek God Zeus:

“I shall say to him: ‘It is not my fault that you made me a poet, and that you gave me the gift of seeing simultaneously what was happening in Omaha and Prague, in the Baltic states and on the shores of the Arctic Ocean. I felt that if I did not use that gift my poetry would be tasteless to me and fame detestable. Forgive me.’”

He died August 14, 2004 at his home in Krakow. He was 93.

In recalling his youth in Lithuania, he writes in The Captive Mind: “The first sunlight I saw, my first smell of the earth, my first tree, were the sunlight, smell, and tree of these regions; for I was born there, of Polish-speaking parents, beside a river that bore a Lithuanian name.”

In a 1980 poem called “The River,” perhaps reminiscent of happier times and of that river he grew up near—the Niewiaza River—or perhaps all rivers, he writes:

I hear in myself, now as then, the lapping of water by the boathouse

And the whisper that calls me in for an embrace and for consolation.

We go down with the bells ringing in all the sunken cities.

Forgotten, we are greeted by the embassies of the dead,

While your endless flowing carries us on and on;

And neither is nor was. The moment only, eternal.

Selected Bibliography

Franaszek, Andrzej. Milosz: A Biography. Edited and translated by Aleksandra and Michael Parker. Cambridge, Mass. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017

Milosz, Czeslaw. The Captive Mind. Translated from the Polish by Jane Zielonko. New York, N.Y. Vintage International, 1990.

Milosz, Czeslaw. New Collected Poems: 1931 - 2001. New York, N.Y. Ecco, 2017.

Peck, M. Scott. People of the Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil. New York, N.Y. Simon & Schuster, 1983

This is the fourth edition of Underlined Sentences. If you missed the three previous editions, you can read them here, here, and here.

My goal with this column is to offer thoroughly researched, informative, and insightful observations on the “underlined sentences” of both timely and timeless books or other written documents that I feature. I offer a brief sketch of the writers and place their texts—books, essays, poems, scripture—in the context in which they were written.

I also explore how they are relevant to our lives today. And I reflect on how they have challenged me to think about my life and how I can tap into their wisdom to get to the heart of the difficult matters that increasingly plague us, and to help guide us through them, if only by holding each other in an emotional and intellectual embrace. These columns take a considerable amount of time to research and write, so I’m posting them once every few weeks.

Up to now, I’ve been featuring writers of the WWII and post-war era. They warned us about the dangers of Marxism looming then in Europe and here in America, a threat which continues today on both sides of the Atlantic. But now it is not dressed in jackboots and stiff uniforms, but in the garb of everyman, especially the past four years under President Joe Biden. This edition on The Captive Mind by Polish writer Czeslaw Milosz continues along these lines.

Please comment, share, and subscribe (see link below). Subscriptions are free, although there is a paying option. Or you can make a one-time contribution by clicking on the “Buy me a coffee” button below for options. And, as always, thank you for reading. I would love to hear from you. If you’d like to contact me, email me: jimkullander@gmail.com

Each of your essays is commendably clear, thought-out, researched, and organized -- a lot of scholarly labor! Rather refreshing in the fragmented, incoherent land of the interwebz. And your opening story is powerful! This article resonates with my own disappointment in the community of writers to which I once felt attached... whose minds are now captive. I suppose they always were, and maybe mine was as well. But with constant, earnest vigilance, observing the world and questioning every detail of my reaction to it, somehow I escaped. I am grateful.

So much empathy, so much pain, and yet so much in your essay for anyone who wishes to pause and reflect to awaken within to so much of goodness that lies within each one of us and the each one of us have the God-given resource to make the world around us through words and acts truly a heaven for ourselves and those with whom we live. I am reminded of William Blake's verse, "To see a world in a grain of sand / And a heaven in a wild flower, / Hold infinity in the palm of your hand / And eternity in an hour." I read Milosz's "The Captive Mind" almost 50 years ago about the same time I was reading Solzhenitsyn. I survived and escaped from a genocide in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in 1971 as a teenager, and circumstances (providence) brought me to North America. I am now retired from the academia as professor emeritus in Canada, but have lived in America. When I came in the early 1970s the Vietnam War was raging, Nixon was the president, but like you, the author of this essay, I was ecstatic that I was in the land of the free and the brave, and the future was open to me as a gift that I might not be deserving. I worked at odd jobs, never complaining, became a cab driver as I went through university and earned a doctorate and became a resident of the ivory tower. I travelled through much of the Global South, sharing and learning and reading what I could bring back to my students. When the Cold War ended I took the risk in 1993 with another friend to head for a land journey across China and Russia on the Silk Road which we did and saw behind the Iron Curtain how the people had suffered and survived, and that they had got the chance to repair their past and make a better future. This journey my friend and I made, and escaped as you did without getting arrested and thrown into some unknown dungeon, was that of two individuals who were young and foolhardy and ready to take risk into going into the unknown that the inner lands of the Soviet Union and China had been to outsiders. I came back richer and more thankful of being gifted a life to live in North America and make here home for myself and the family I raised.

For the gift of becoming a North American at a personal level I remain ever grateful to my Lord, though I now see even more clearly how great has been the inversion here of turning this continent into its opposite, its own version of a totalitarian entity against which the United States built its self-image by copious propaganda of the Cold War decades. In researching the genocide from which I escaped the role of the U.S. emerges in terrifying details, of the strategic support given to the Pakistan army and the military regime of General Yahya Khan by Nixon-Kissinger duo to do the mass killings, as the U.S. did in the open carnage of Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia, East Timor through the sixties into the eighties. America has not been held to any accountability for the destruction of lives and countries during those decades, while Americans prospered at home through these never-ending wars abroad. And so once the eyes of anyone with a scintilla of humanity opens, as were those of Milosz, there is no shutting of those eyes as the perspective in terms of global history widens and the reality sinks in that America is no less faultless in doing ill to others as were those countries such as Nazi Germany and Communist Russia against whom most Americans measure themselves for being good against evil.

Few Americans know, or seem to want to know, about others and what in their name their leaders have done to those others simply because they were in their way in pursuit of America's global ambition to be the overlord in the world. "As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods; / They kill us for their sport", so wrote Shakespeare in King Lear. Yes, this is how the powers to be in Washington, in Moscow, in London, in Paris, in Berlin, in Tokyo and elsewhere have conducted themselves, while some powers are limited within their own confined circles and others, such as America, rages far beyond its oceans and continents, to bring death and destruction to others whose lives meant for Americans to be as worthless as summer flies are in their own fields which Americans lay claim and proceed to empty it for themselves.

I am not a Christian, but then I am someone who reveres Jesus and his other Mary, as the Quran, the scared book of Muslims, reveals to me being a Muslim that they were God's most special creations. Most American Christians who are a majority among Americans are sadly ignorant of this simple fact about Muslim faith and their reverence for Jesus. For me the most important message of Jesus's ministry is about love, sacredness of life, the golden rule, and all of it wrapped together in those simple words "take the beam out of your eye" and "blessed are the peacemakers, for they are the children of God." If only American Christians simply, truly, honestly, adhered to these words of Jesus in living with others, they would make the difference between war and peace, and there would be peace as Jesus called for among us around the world and we could settle our differences or live despite those differences in peace without becoming "captive minds" of our totalitarian masters.

God bless.